by Sonia Badiali and Valeria Calderoni. Leggi in Italiano

Here we are, ready to dive once more into the wonderful world of spaghetti western! A few weeks ago, in the first part of the article, we listed the best spaghetti western movies according to Mik, who gave us a great introduction to the origins of the genre: we started with the best, unforgettable classics by founding father Sergio Leone and went on to discover some great films by like-minded directors who took inspiration from his style, perspective and attitude towards western cinema, first and foremost Clint Eastwood.

Today, however, we are going to explore the bloody, violent and ruthless side of Italian western. Not only do these movies, much like the classics previously mentioned, show us the brutal side of the West and the bitter reality of life, where things don’t always end well, heroes are not always spotless and villains are not necessarily defeated – but they do so with a vengeful slap in the face of the viewer, as to wake him up and tell him: “Did you ever really think that things could be any different that what we are about to show you? You miserable fools!”

The merciless, punishing intent to wean the naive audience and the growing tendency to linger on the tragic details of life in the Wild West are definitely the defining traits of the evolution of spaghetti western from Leone’s violent but still poetic beginnings to the blunt, ferocious tones of Corbucci, Sollima and Petroni. These feature films tend to polarize western movie audiences still today between those who embrace the stark rejection of the classic western tradition of John Ford and co. in its romanticization of the mythology of the west and those who are unimpressed at best – if not outright disgusted – by the relentless and explicit violence that is used, in their opinion, to hide a lack of mastery and imagination on the part of the filmmaker.

Luca, the member of our family who more than any other knows and loves this particular incarnation of the western movie landscape, definitely belongs to the first group: but where do we stand, readers and friends?

Luca kindly offered us a list of the best spaghetti western of the bloody type: ten movies that prove the mastery, poetry and abilities of our Italian directors alongside their love of gore; ten masterpieces that were honored by the presence of some of the most celebrated actors of the genre as well as by original scores by none other than maestro Ennio Morricone; ten controversial, fascinating films that will put our taste, our prejudice and our guts to the test!

THE WEST ACCORDING TO LUCA:

10 Spaghetti westernS “AL POMODORO”

| Titolo | Regista | Anno |

|---|---|---|

| Keoma | Enzo G. Castellari | 1976 |

| The Great Silence | Sergio Corbucci | 1968 |

| The Big Gundown | Sergio Sollima | 1966 |

| Face To Face | Sergio Sollima | 1967 |

| Run Man Run | Sergio Sollima | 1968 |

| Blood and Guns | Giulio Petroni | 1969 |

| Day of Anger | Tonino Valerii | 1967 |

| Massacre Time | Lucio Fulci | 1966 |

| A Bullet for the General | Damiano Damiani | 1966 |

| Django, Prepare a Coffin! | Ferdinando Baldi | 1968 |

Keoma by Enzo G. Castellari, 1976

with Franco Nero, William Berger, Olga Karlatos; 101 min.

Keoma (Nero), son of a white man and an Indian woman, seeks to return to his country after the Civil War. During the journey, Keoma encounters a wagon train of plague victims, escorted by a group of gunmen who lead them to their deaths in an abandoned mine. Among the prisoners, Keoma meets a healthy pregnant woman and sets her free. The woman tells him about the current situation in the village, where former army officer Caldwell is in charge after forcing all the farmers to sell their land. Upon reaching his father (Berger), he reveals that his half-brothers, who have always hated him, have allied themselves with Caldwell.

The movie revolves around Keoma’s attempt to save the village and the pregnant woman, managing to showcase Castellari’s ability to develop a typical western theme in a unique and original way, by proposing biblical and political themes uncommon for the genre. Death, represented by an old witch dragging a cart and appearing every time Keoma’s time seems to be approaching, is the most intriguing supporting character in the movie. Overall, an absolute masterpiece, and our favorite on the list.

The Great Silence by Sergio Corbucci, 1968

with Jean Louis Trintignant, Klaus Kinski, Vonetta McGee; 105 min.

A group of bandits are hiding in the snowy forests of Utah and waiting for the upcoming amnesty that would relieve them of unfair accusations, but they are hunted down and killed by a group of bounty hunters summoned by justice of peace Pollicut and led by Tigrero (Kinski). Pauline (McGee), whose husband was killed by Tigrero, hires relentless mute gunslinger Silence (Trintignant) to avenge his death. Silence owes his inability to speak to the throat wound inflicted upon him by the bounty hunters who killed his parents, and owes his name to the rumor that “after he’s passed through town, nothing is left but the silence of death”.

A bond is established between Silence and Pauline which goes beyond their simple business agreement, as the woman offers comfort and support to Silence until the very last moment, when he will face the bloodiest and most terrible of his battles.

Filmed entirely in Italy, the film was rated X, thus limiting its distribution and box office success – but this did not prevent it from becoming one of the greatest timeless classics of Italian western.

The Big Gundown by Sergio Sollima, 1966

with Lee Van Cleef, Tomas Milian as Manuel “Cuchillo” Sanchez, Walter Barnes; 108min

A landowner offers gunslinger Jonathan Corbett (Van Cleef) support for his candidacy to the Senate in exchange for Corbett’s support for his construction plan for a railroad that will cross the United States all the way to Mexico. The gunslinger is about to accept the deal when he is instead assigned the task of capturing Cuchillo (Milian), a young Mexican accused of raping and murdering a 12-year-old girl. As it turns out, Cuchillo doesn’t let himself get caught easily, and through his series of failed attempts Corbett learns that Cuchillo is innocent.

Sollima gave Cuchillo a strong political connotation: a romantic, anarchist antihero who prefers the dagger, a poor man’s weapon, to the gun. He eventually became a rebel teen idol of the likes of James Dean, in particular due his most famous line: “You will never catch me… Cuchillo leaves!”

The final showdown is considered one of the most beautiful in western movie history, and is accompanied by a stunning soundtrack by Ennio Morricone, which incorporates Beethoven’s “Per Elisa” in a classic western-style musical theme.

Face to Face by Sergio Sollima, 1967

with Gian Maria Volonté, Tomas Milian, William Berger; 108 min.

A history professor ill with consumption (Volonté) travels to Texas for treatment, but is taken hostage by a band of outlaws. The educated and peaceful professor tries at first to redeem the leader of the gang, Beauregard Bennet (Milian), but slowly learns to appreciate and love the adventurous life of the gang, to which he joins on a permanent basis, becoming so ruthless that the bandit himself will have to stop him.

Made unforgettable by the interpretations of Volonté and Milian, the film is a classic by maestro Sollima which draws strength from the ability to illustrate, through the evolution of the character of the two protagonists, how the boundaries between “good” and “bad” are often blurred.

The illustration of the powerful negative charge that an intellectual can conceal behind his cultivated persona, and the professor’s sentence “We must cross the border of individual violence, which is considered a crime, to get to mass violence, which is considered history” was read by many as an inspiration for the actions of professor Toni Negri and his Brigate Rosse leftist terrorist group in Italy in the seventies and eighties. Excellent soundtrack by our beloved Morricone.

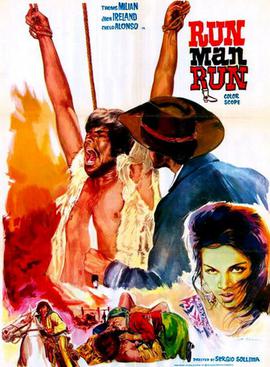

Run Man Run by Sergio Sollima, 1968

with Tomas Milian, Donald O’Brien, Linda Veras; 120 min.

The film is a sequel to The Big Gundown, and takes us back to Cuchillo’s adventures after returning to his hometown in Mexico, where he is soon put in prison and shares a cell with revolutionary writer Ramirez. With both men freed thanks to an amnesty, Ramirez hires Cuchillo to help him escape bounty hunters and recover the three million dollars he hid and intended for the revolutionary cause. With both men freed thanks to an amnesty, Ramirez hires Cuchillo to help him escape a group of bounty hunters and recover the three million dollars he had hidden and designated for use in the revolutionary cause.

The two arrive at Ramirez’s village, where Ramirez is killed by the ex-revolutionary bandit Reza – but not before managing to convey to Cuchillo the information needed to recover the money to be returned to the revolutionary leader, Santillana.

Cuchillo sets out on a journey to fulfill the mission, facing deceptions, ambushes and betrayal by his numerous opponents, who want to get their hands on the gold – including his fiancée Dolores, who pursues him in the hopes of convincing him to abandon the venture.

Blood And Guns by Giulio Petroni, 1969

with Tomas Milian, Orson Welles, John Steiner; 132 min.

Jesus Maria Moran a.k.a. Tepepa (Milian) is deeply disillusioned with the government of President Madero, once a revolutionary himself, and continues to fight for the revolution along with a group of loyal fighters. In the meantime, Tepepa is repeatedly confronted by Colonel Cascorro (Welles), a commander of the Rurales who wants to shoot him, and an English doctor, Henry Price (Steiner), eager to avenge a girl he was in love with and who Tepepa had raped, causing her to commit suicide.

One of the best spaghetti westerns dedicated to the Mexican revolution, Tepepa explores anti-colonialist themes and embodies the 1968 idealism typical of the period. One of the most interesting moments of the film is Tepepa’s monologue about the “betrayed revolution”, which expresses the people’s disappointment with the hypocrisy of the revolutionary leaders and the awareness that power always ends up corrupting those who take it into their hands. Brilliant also the choice of soundtracks, which climbs in intensity as the narrative progresses.

Sad fun fact: Tomas Milian couldn’t wait to meet Orson Welles, who was his hero, on the set of Tepepa – but the encounter was a terrible disappointment, as reported by Marco Giusti in an article on Italian newspaper La Repubblica. According to his account, “Welles called [Milian] a ‘dirty Cuban’ and if he asked him which way to stand, he replied ‘wherever you like, as long as I don’t see your face’.”

Day of Anger by Tonino Valerii, 1967

with Giuliano Gemma, Lee Van Cleef, Walter Rilla, Christa Linder; 111 min.

Scott (Gemma) is an orphaned and marginalized street sweeper who lives in a small Arizona town and dreams of becoming a gunslinger. When mysterious stranger Frank Talby(Van Cleef) arrives in town, Scott finds in him an advocate against the abuses of the corrupt citizens who taunt him, as well as a master in the art of gun handling. Soon the two are ridding the town of their enemies, but Scott has to choose between supporting Talby, who is determined to take control of the town, and his friend Murph Allan, who has become sheriff and saved his life several times.

Another exciting Italian western which applies the lessons of master Leone with sublime results, focusing on the desire for revenge and the exploration of the complex relationship between the protagonists played excellently by Gemma and Van Cleef.

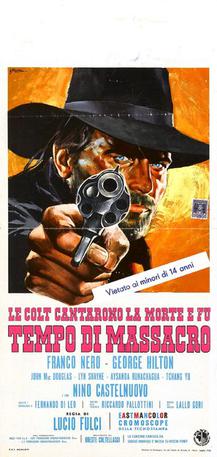

Massacre Time by Lucio Fulci, 1966

with Franco Nero, George Hilton, Nino Castelnuovo; 83 min.

Gold prospector Tom Corbett (Nero) returns to his hometown after many years and finds the family farm destroyed and robbed by landowner Scott (Castelnuovo); his brother Jeff (Hilton), embittered by the alcoholism in which he has taken refuge after the death of his mother, tells him to leave. Tom, however, is determined to redeem his brother and avenge the loss of the family farm, and convinces Jeff to assist him in the fight against Scott and his sadistic son Junior.

At his debut in the western, Fulci had until then devoted himself to comedies, music videos and erotic films; the turning point that led him to find his unmistakable style, which made him one of the most celebrated Italian directors of crime and horror films, came with this film, which Fulci called “Artaudian”, referring to the lessons he learned from Antonin Artaud’s theory of the “theater of cruelty”.

Violence abounds in the film: bordering on the splatter genre, including scenes of rape, cannibalism and skinning, Massacre Time is one of the most violent films ever in the history of western cinema, second only to Four of the Apocalypse, directed by Fulci in 1975.

A Bullet For The General by Damiano Damiani, 1966

with Gian Maria Volonté, Lou Castel, Klaus Kinski; 118 min.

At the time of the Mexican Revolution, Bill Tate (Castel), an American hired gun sent to kill General Elías, joins a gang of revolutionaries led by Chuncho (Volonté), who renames him “Niño”.

During a holiday break in a liberated village, Niño convinces Chuncho’s gang to flee with the stolen weapons before the arrival of the attacking army, leaving him alone with his brother Santo (Kinski) in the arduous task of defending the town’s peasants. Chuncho’s vain attempt to retrieve the weapons causes the village to be exterminated in his absence, but the trip in the company of Niño allows the latter to appreciate Chuncho’s good nature, prompting him to revise his plans.

Considered an “American-style” spaghetti western for Damiani’s ability to combine Leone’s atmospheres with the violence typical of Peckinpah’s films, A Bullet For The General breaks away from the western tradition with its anti-American themes and its ability to create complex antagonists with their own moral code – a characteristic, the latter, incorporated by Leone only starting in 1971 with Duck, You Sucker!, also set in Mexico.

Django, Prepare a Coffin! by Ferdinando Baldi, 1968

with Terence Hill, Horst Frank, George Eastman; 88 min.

Senator David Berry (Frank) is running for county governor and asks his friend Django to offer him his support until the election, but he is busy escorting a load of gold to the federal depository in Atlanta.

During the journey, a gang of criminals under Berry’s command attacks and exterminates the convoy, killing also Django’s wife. He then fakes his own death and assumes a new identity as the county executioner, trying to protect the victims of Berry’s abuses while preparing his bloody revenge.

Also known by the title of Viva Django!, The film is presented as a prequel to Corbucci’s original Django, despite Franco Nero’s refusal to reprise the lead role, which was then assigned to Terence Hill.

Immagine di copertina: Lago di Camposecco, Piemonte, Italia; foto di Rosa Amato.