Starting from the 1960s, widespread protests began to take shape against the dominant cultural framework that had guided American society until then, condemning also the atrocities perpetrated by the American army in the Vietnam war. In the context of Western movies, the myth of the conquest of the West began to crumble, the boundaries between good and evil became increasingly blurred, and movies began to portray the culture of Native Americans more faithfully. The violence of the American army against them, usually hidden behind a patina of heroism in the defense of “civilization” against the “savages”, allowed the directors to draw a parallel with the hypocrisy of society in their time. Needless to say, the comparison is more valid than ever nowadays.

The respectful representation of Indian culture is only one of the aspects of so-called Western “revisionist” cinema, which expanded in the direction of various themes and subgenres; with this list, however, we want to focus on ten of the best films dedicated to Native American culture, carefully chosen by Mik as his favorites. The message that many of these films convey, in Mik’s own words, is that “the only way to achieve peace between peoples lies in mutual understanding and in the awareness that there are shared human values beyond selfish motivations and cultural differences. It is therefore important to understand each other’s needs, and the message is more valid than ever in our days”.

Many of us became aware of the genre thanks to the award-winning 1990 film Dances With Wolves and perhaps through Soldier Blue, known for having been censored in many countries due to its extreme violence; but the first western films that portrayed Indian tribes not as the enemy but as people fighting for their culture, their traditions and their survival came out in 1950, with Delmer Daves’s Broken Arrow and Devil’s Doorway By Anthony Mann. Robert Aldrich’s 1954 film Apache was the first to feature an Indian warrior as the main character. Follow us in our journey to discover these and other Western masterpieces focused on Native American culture!

Mik’s choice of Western Movies:

10 Best FILMs ON NATIVE AMERICANs

| Title | Director | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Broken Arrow | Delmer Daves | 1950 |

| Apache | Robert Aldrich | 1954 |

| Cheyenne Autumn | John Ford | 1964 |

| Little Big Man | Arthur Penn | 1970 |

| Soldier Blue | Ralph Nelson | 1970 |

| A Man Called Horse | Lee J. Thompson | 1970 |

| Jeremiah Johnson | Sydney Pollack | 1972 |

| Dances With Wolves | Kevin Costner | 1990 |

| Last Of The Mohicans | Michael Mann | 1992 |

| Geronimo: An American Legend | Walter Hill | 1993 |

Broken Arrow by Delmer Daves, 1950

With James Stewart, Jeff Chandler, Debra Paget; color, 93 min

Tom Jeffords (James Stewart) becomes a friend and blood brother of a young Apache boy, and is frowned upon by whites who consider him a traitor and try to lynch him. He is rescued by General Howard, who persuades Tom to follow him along to the Apache camp to formulate a peace agreement with Chief Cochise. But among the white people there are some those who, driven by personal interests, do not want peace to prevail.

Taken from Elliott Arnold’s 1947 novel Blood Brother, the film won the 1951 Golden Globe Award for Best Film Promoting International Understanding, and gave rise to two sequels: 1952’S The Battle at Apache Pass and 1954’s Taza, Son of Cochise.

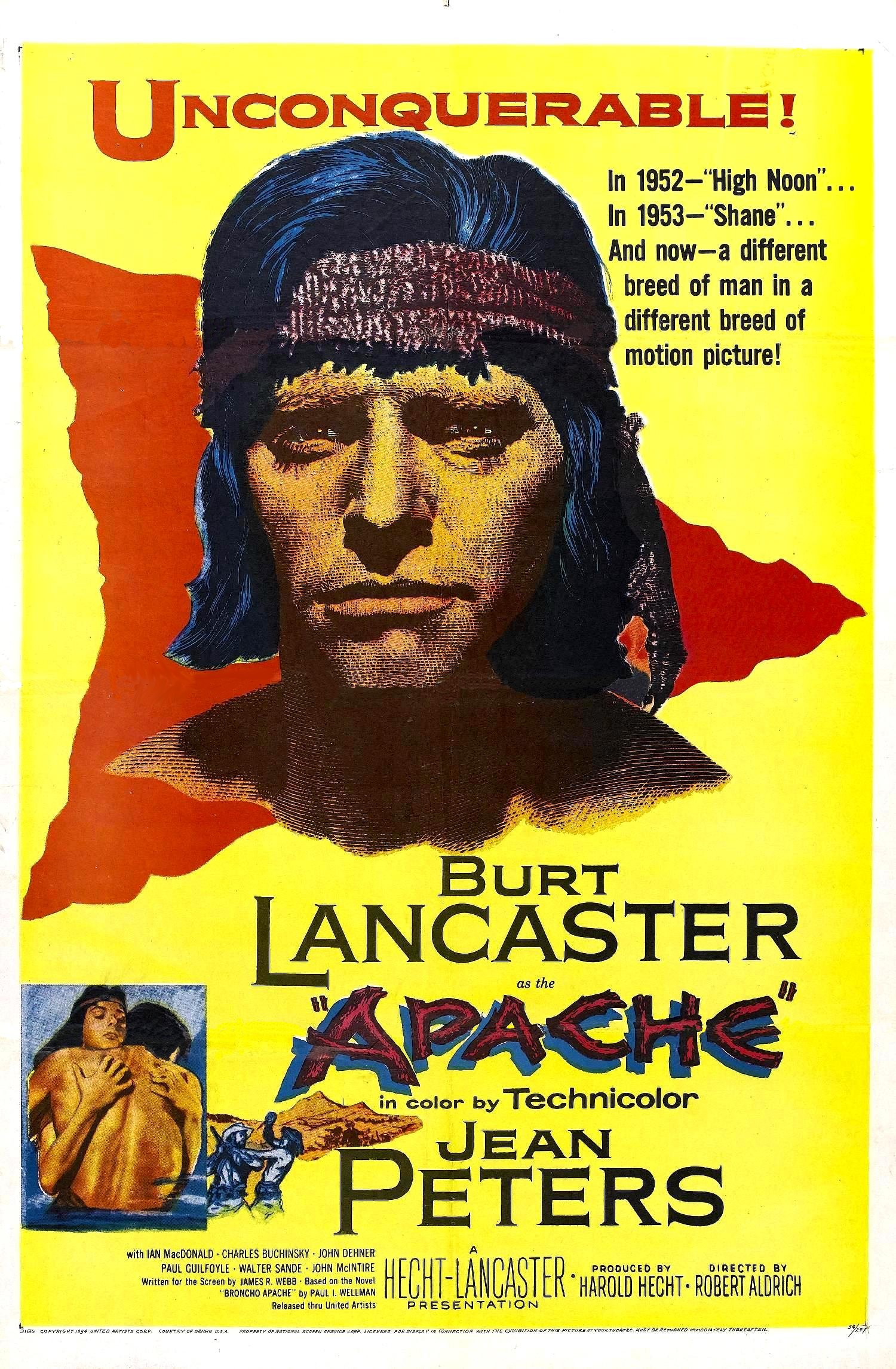

Apache by Robert Aldrich, 1954

With Burt Lancaster, Jean Peters, John McIntire; color, 87 min

After the defeat and surrender of Geronimo, the last chief of the Apache tribe, the members of his tribe let themselves be led to the reserve destined for them in Florida. Only the young Apache Massai refuses to surrender and manages to escape with his partner, resisting the fate assigned to him by the whites and becoming legend.

Inspired by the novel Bronco Apache by Paul I. Wellman, Apache is the first of six western movies that Aldrich shot with Burt Lancaster. Both wanted the ending to be faithful to the book, where Massai is killed by a consanguineous traitor, but Aldrich had to submit to the will of the production, which wanted to propose a more optimistic ending.

Cheyenne Autumn by John Ford, 1964

With Richard Widmark, Carroll Baker, Ricardo Montalban; color, 154 min.

Exhausted by hunger and cold in the Oklahoma Indian reservation, the Cheyenne set off to return to Wyoming, facing an impervious march of 2,000 kilometers through deserts and snow storms that leaves them decimated. When they are reached by the soldiers of Captain Archer, who are sent to mediate an agreement, two parties begin a negotiation that does not interest neither politicians nor the military and is distorted by the press. The only ones who take the fate of the Indians to heart are Captain Archer, Quaker teacher Deborah and the US Secretary of the Interior. The adversities faced create divisions even among the Cheyenne, leading to a fratricidal struggle.

The screenplay for the film was taken from the books Cheyenne Autumn by Mari Sandoz and The last Frontier by Howard Fast. This latest western from Ford, based on a true historical fact, was represented by Ford as a form of moral compensation towards Native American tribes that he had often potrayed as ruthless savages in his films.

Little Big Man by Arthur Penn, 1970

With Dustin Hoffman, Faye Dunaway, Chief Dan George; color, 139 min

Ultra-centenarian Jack Crabb tells the story of his life to a journalist. Having survived the massacre of his family thanks to a Cheyenne who saved him and took him to his village, Crabb – nicknamed “Little Big Man” for his courage in fight – chooses to continue living with the tribe that welcomed him.

The extermination of his village by the American army, however, forces him to return to live among the white people. After several failed attempts at integration, and having witnessed further massacres perpetrated by the US army, Little Big Man decided to avenge his tribe, thus contributing to the defeat of General Custer at Little Big Horn.

Based on the novel Thomas Berger novel, the character of “Little Big Man” was based on an Oglala Sioux tribal chief who had little in common with the invented character of Jack Crabb.

Soldier Blue by Ralph Nelson, 1970

With Candice Bergen, Peter Strauss, Donald Pleasence; color, 112 min

The film tells the story of Cresta Lee, a white girl who after being kidnapped and spending 2 years in a Cheyenne tribe, is freed by American soldiers and travels with them to finally join and marry her fiancée in the army camp to which he is assigned. The soldiers, however, are ambushed and killed by the Indians, leaving Cresta and young “soldier blue” Honus alone in the attempt to reach the fort.

During their trip, Cresta shows Honus the point of view of the Indians, justifying their violence as self-defense. Kathy and Honus then witness the Sand Creek massacre, one of the most notorious episodes of the Indian wars, during which a village of about five hundred defenseless Cheyenne and Arapaho were killed and maimed by the American army.

The massacre is portrayed in the film in all its brutality, and the film caused a sensation for its scenes of explicit violence that constituted a denunciation of the abuses of the American army, not only against the Indians but also in the raging Vietnam War, of which the film constitutes a clear allegory and denunciation.

A Man Called Horse by Elliot Silverstein, 1970

With Richard Harris, Judith Anderson, Jean Gascon; color, 114 min.

English aristocrat John Morgan is taken prisoner by the Sioux during a hunting trip with three friends, who are immediately killed. Morgan is instead taken to the camp and entrusted to the mother of the Yellow Hand tribe chief to be used as a workhorse.

Thanks to the help of Batise, prisoner in the camp since years and maimed for trying to escape, Morgan learns the language and culture of Indians, managing over time to fully understand those customs that until then had seemed “barbaric” to him. After a tough initiation ritual, he is accepted by the Sioux as a warrior with the name of “Shunka Wakan” (“the man called horse”) and takes part with them in a bloody battle against their Shoshone enemies.

Despite the attempt to present Sioux culture for the first time in an authentic and faithful way, the film still transmitted an unequivocally “white” point of view and, due to various inaccuracies in the representation of the Sioux, was not well received by the Native American community. Nonetheless, the movie is appreciated for the numerous dialogues in the original Sioux language and for the photography of Robert B. Hauser, who also worked on Soldier Blue the same year.

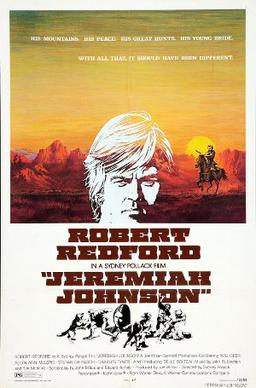

Jeremiah Johnson by Sydney Pollack, 1972

With Robert Redford, Will Gear, Delle Bolton; color, 108 min.

Jeremiah Johnson, a veteran of the Mexican-American war, chooses to retire to a solitary life in the Rocky Mountains to live in the manner of trappers, pioneer explorers that lived as hunters and fur-traders. The first harsh winter in the mountains finds him unprepared, but thanks to the help of the eccentric veteran Chris Lapp, he acquires the knowledge necessary for survival.

Proceeding alone in his explorations, he adopts the silent child of the only survivor of an attack by the Blackfoot, marries the daughter of an Indian chief and dedicates himself to taking care of his family until he is asked by US army to help leading a group of isolated settlers out of danger. While doing so, he is forced to cross a sacred cemetery of the Crow Indians, who take their revenge on him by killing his wife and child. Mad with grief, Jeremiah Johnson devotes the rest of his life to killing his enemies down to the last warrior, thus earning himself the respect and admiration of the Crow themselves, who erect a monument to his courage.

The movie is based on the story Crow Killer by Raymond Thorp and on the novel The Mountain Man by Verdis Fisher, both dedicated to the life of John “Liver-Eating” Johnson, a legendary mountain man of the American West. The film was shot in impervious areas of Utah; to reach the locations, the troupe traveled over twenty-six thousand miles with all the equipment. To meet the rising costs of production due to the delays in the schedule, Redford and Pollak personally financed the film.

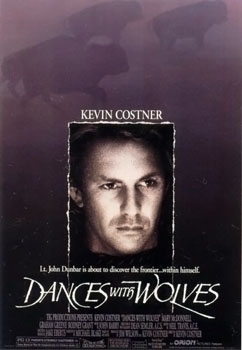

Dances With Wolves by Kevin Costner, 1990

With Kevin Costner, Mary McDonnell, Graham Greene; color, 181 min. (theatrical release version)

At the time of the Civil War, Lieutenant John Dunbar, seriously injured during a battle in Tennessee, performs an act of extreme courage that leads Union forces to victory. As a reward for his value he is given the opportunity to be transfered wherever he wishes; after choosing a border garrison, Dunbar is sent to Fort Sedgewick, which he finds abandoned.

After spending the first weeks in the exclusive company of his horse and a wolf who becomes his friend, he establishes a dialogue with the Sioux Lakota tribe, who are engaged in fighting with the neighboring enemy tribe of the Pawnees. Life in close contact with the Lakota leads him to understanding their problems and sharing their customs and traditions, to the point of learning their language and marrying the adoptive daughter of the tribe’s medicine man. In the eyes of the US military, however, Lieutenant Dunbar is now considered a traitor and hunted as such.

Based on the novel of the same name by Michael Blake, who also wrote the screenplay for the movie, which went on to win seven Academy Awards: best film, best director, best non-original screenplay, best photography, best editing, best sound and best dramatic soundtrack.

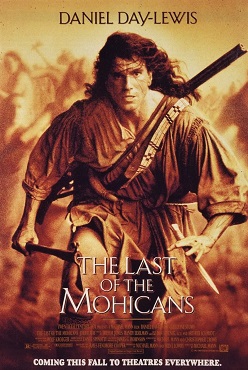

Last Of The Mohicans by Michael Mann, 1992

With Daniel Day Lewis, Madeleine Stowe, Jodhi May; color, 117 min.

On the North American front of the Seven Years’ War, Indian tribes find themselves fighting on opposite sides: many have allied themselves with the French army, others, such as the Cherokee and Mohawk, fight on the side the British army instead. In this context, the film focuses on the life of the last surviving members of the Mohican tribe: Chingachgook, former tribal chief (Daniel Day Lewis), his son Uncas and a young Englishman named Nathan Hawkeye whom Chingachgook adopted as a child when his family was exterminated.

The three live in peace by hunting in the forest and maintaining good relations with the British thanks to the help of Nathan who speaks their language. Headed West to escape the war, they find themselves rescuing a British escort party including the daughters of Commander Munro, attacked by the Urone tribe led by the ferocious Magua. The attack is a personal revenge of Chief Urone towards commander Munro, guilty of killing his children. During the various clashes the two Mohican brothers fall in love with the English captain’s daughters and do everything in their power to save them when the Hurons capture them after killing their father.

Based on the book of the same name by James Fenimore Cooper, the film won an Oscar for the soundtrack, and is still considered a masterpiece of the genre today. Daniel Day-Lewis underwent intense preparation to play the role of Chingachgook, and spent months living out of his own hunting and fishing in the territories where his character was supposed to live. After filming was completed the actor had to seek treatment for claustrophobia and hallucinations.

Geronimo: An American Legend by Walter Hill, 1993

With Jason Patric, Gene Hackman, Wes Studi; color, 115 min

Due to his knowledge of Apache language, Lieutenant Charles Gatewood is commissioned by General Crook to escort Indian chief Geronimo to safety at the fort. After facing a group of Texans who want to kill Geronimo, the two develop a sincere friendship. Unfortunately, however, the truce between the US army and the Indians is broken and Geronimo flees to Mexico and organizes groups of Indians who massacre settlers on the way.

General Crook is replaced by General Miles, who isolates Gatewood and his colleague Britton Davis, fires the Indian guides and sends five thousand soldiers to defeat a small Apache group and their families. Determined to find Geronimo, the general secretly asks Gatewood to track him down and offer him an honorable surrender.

According to the director himself, the film set out to narrate the complexity of the historical events surrounding Geronimo’s surrender in a reliable and thorough manner, and was well received by Native American communities at the time of release.

Geronimo is played by Wes Study, an American Indian actor from the Cherokee tribe who also played the fierce warrior Magua in the movie The Last of the Mohicans and a Pawnee warrior in Dances With Wolves.

Header image: Mt. Timpanogos Sunset, Wasatch Range, Utah, by Curtis Fry.